Synopsis

Richard Clarke (Benny), a small town lawyer, is not making enough money to marry Janie Brown (Lane), his fiancée. To improve himself, Richard moves to New York City. Although he does not have any clients, Richard tells Janie that he is doing well. She expects to move to New York and marry him.

His assistant Shufro (Anderson) suggests that he could make some money if he

became hard and ruthless. The ultimate test of his meanness is 'stealing candy

from a baby'. He is photographed as he pulls a sucker away from a small boy. The

picture is printed in the paper under the caption,

Meanest Man in the World.

He is hired to evict an old woman, Mrs. Frances

H. Leggitt (Margaret Seddon), from her apartment and more pictures appear in the

paper.

Actually, he has taken Leggitt into his own apartment. Janie visits and, believing

what she has read about how mean

Richard has become, leaves angrily. A

misunderstanding about the lady living in his apartment leads to a headline about

Richard’s love nest.

Janie’s father Arthur (Briggs), thinking that his

daughter is living with Richard, arrives to protect his daughter. A shotgun

marriage follows. Arthur declares that his new son-in-law will return to their

small town and become the respectable attorney for the local bank.

Discussion

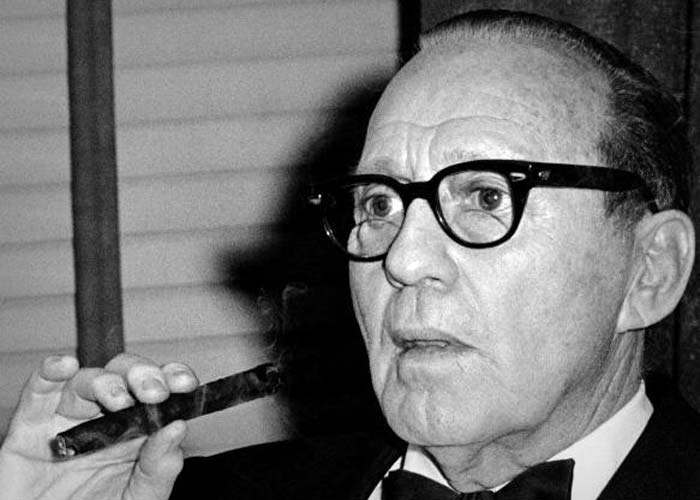

The Meanest Man in the World is, for the most part, a pleasant

vehicle for Jack Benny which conforms to his established persona. The plot and the

comedy develop slowly. The film becomes laugh-out-loud funny about halfway through

when hard-hearted

Benny struggles with a boy over a lollipop and evicts the

old lady. The comedy declines after these hilarious scenes, particularly during an

unfortunate scene with Benny in blackface, and the film ends abruptly with the

forced marriage. (For a high-budget production, intended for a well-advertised and

important release, the film is quite short at 57 minutes. The paucity of story

content is probably the result of several major script revisions and scene

deletions that occurred during filming.) The droll exchanges between Benny and

Eddie 'Rochester' Anderson would have been familiar to audiences due to the

popular The Jack Benny Program radio show, which aired from 1932-55.

Priscilla Lane, pretty and appealing, pairs easily with Benny, although the

twenty-year age difference is obvious.

Benny had a three film deal with 20th Century Fox, appearing in one film per year. A film based on a 1920 play The Meanest Man in the World was suggested for Benny in early 1942, who approved of the concept. Morrie Ryskind, comedy writer for theater and film, was hired to write the screenplay. Filming was scheduled to start in July 1942, but Benny had objections to the script, which he thought was not funny enough and did not fit his brand of comedy. Production was suspended for fifteen hours because Benny refused to go ahead. Producer William Perlberg and Darryl Zanuck, head of 20th Century Fox, discussed the situation with Benny and agreed to make changes. George Seaton was brought in to revise the script. Several sequences were cut out. Filming resumed under the direction of Lanfield and was completed by early September 1942. In November retakes and more script revisions, including added scenes, were directed by Ernst Lubitsch. Morrie Ryskind wrote some of the new material. On screen, only George Seaton and Allan House are credited with the screenplay; Ryskind does not receive a credit.

Reviews for The Meanest Man in the World were tepid.

Variety dismissed the film as

short, careless, and hashed-up with a sudden ending on a shotgun wedding.

The New York Times described the film as a featherweight comedy

and

notes that

Jack Benny and the trusty Rochester…put the piece across by sheer dint

of personality.

Jack Benny was successful in vaudeville and in film, but his enduring fame comes from radio. The Jack Benny Program, known to audiences everywhere, was one of the most popular radio shows for more than twenty years. His television show, also called The Jack Benny Program, debuted in 1950 and remained popular until it ended in 1965. Benny had a fifteen-year film career that began in 1930. His earliest films were comedies and musical reviews. By the mid-1930s, his radio popularity brought the public to his movies. Although most of his films are pleasant and undistinguished, Benny made three first-rate films: the superior comedies Charley’s Aunt (1941) and George Washington Slept Here (1942), and Ernst Lubitsch's comedy masterpiece To Be or Not to Be (1942).

The Horn Blows at Midnight (1945), Benny’s final film, is amusing but surprisingly unsettling. Benny, an angel, sets out from heaven to end the world by blowing his trumpet at midnight on a certain day. This apocalyptic comedy, playing in local theaters near the end of World War II, while death and destruction raged across much of Europe and Asia, and starring such a friendly and familiar comedian, must have been disconcerting to contemporary audiences. Benny got a lot of comic yardage from panning this film, which is actually not bad. However, the concept arrived in theaters at the wrong moment, especially for its star. Six months after the release of this film, the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought catastrophic, world-ending events from fiction into fact.

Eddie Anderson was the most famous African-American actor of the 1930s and 1940s.

His fame originated with his continuing role as Rochester van Jones,

valet,

chauffeur, butler, and general household assistant to Jack Benny on Benny’s radio

and television series. Anderson’s role began as a rather conventional black

Pullman porter who interacts with Benny on a trip from New York to Los Angeles.

Anderson’s portrayal was so popular that his character was made a regular on the

radio program. His tart responses to Benny’s miserly and pompous statements added

greatly to the comic effect of the Benny program. Anderson's unforgettable voice

enhanced his radio characterization. The distinctive quality was a rasping,

wheezing, gravelly sound, the result of straining his vocal cords as a

twelve-year-old paperboy. Rochester

was recognized instantly by the

listening audience, the best known and most popular supporting character on

Benny’s program.

Anderson began his stage career in an all-black revue when he was fourteen years

old. For six years he sang and danced in vaudeville with his brother, Cornelius.

He played numerous uncredited film roles. His first featured role was as Noah in

the film version of the Pulitzer Prize-winning play

Green Pastures (1936). He repeated the role in the 1957 television

version of the play. Anderson played the Rochester character in several films,

including Buck Benny Rides Again (1940) and

Love Thy Neighbor (1940). He has a starring role in the all-black

film, Cabin in the Sky (1943), co-starring Lena Horne, Ethel Waters,

and Rex Ingram. In later years, semi-retired, Anderson appeared occasionally on

television in the Rochester

character.

Screenwriter Morrie Ryskind had an unusual career. He began his career writing for the stage, collaborating with George S. Kaufman on the musical comedies The Cocoanuts (1925) and Animal Crackers (1928), written for the Marx Brothers. In the 1930s, Ryskind and Kaufman wrote the books for the George and Ira Gershwin musicals Strike up the Band (1930) and Of Thee I Sing (1933). In Hollywood, Ryskind adapted The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers for film and wrote A Night At the Opera (1935) and Room Service (1938), also for the Marx Brothers. His screenplays for My Man Godfrey (1936) and Stage Door (1937) were nominated for Oscars. Ryskind also wrote the screenplay for Man about Town (1939) for Jack Benny. In 1947, Ryskind testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about supposed communist infiltration and influence in the screenwriter’s guild. He afterward asserted that as a result of this testimony he was professionally ostracized in Hollywood. He became a right-wing political columnist for the Los Angeles Times Syndicate from 1960-71 and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner from 1971-78.