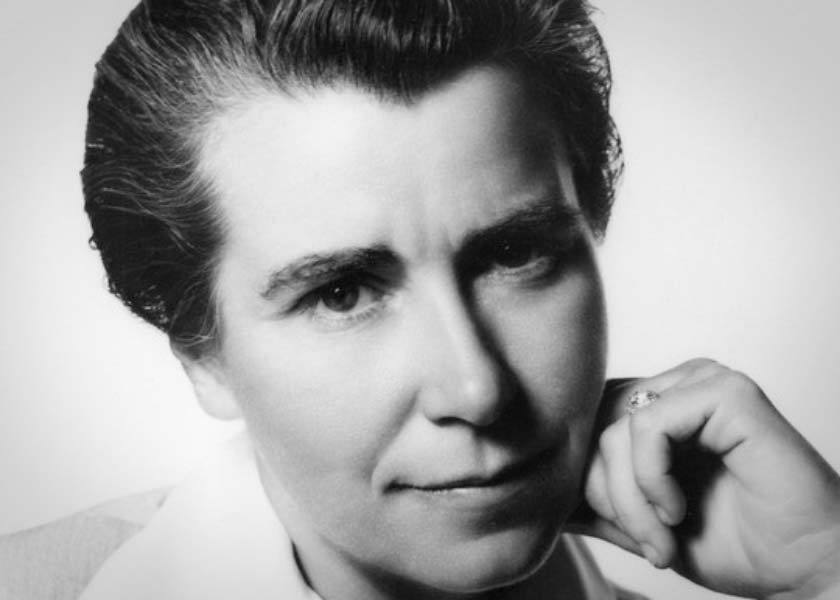

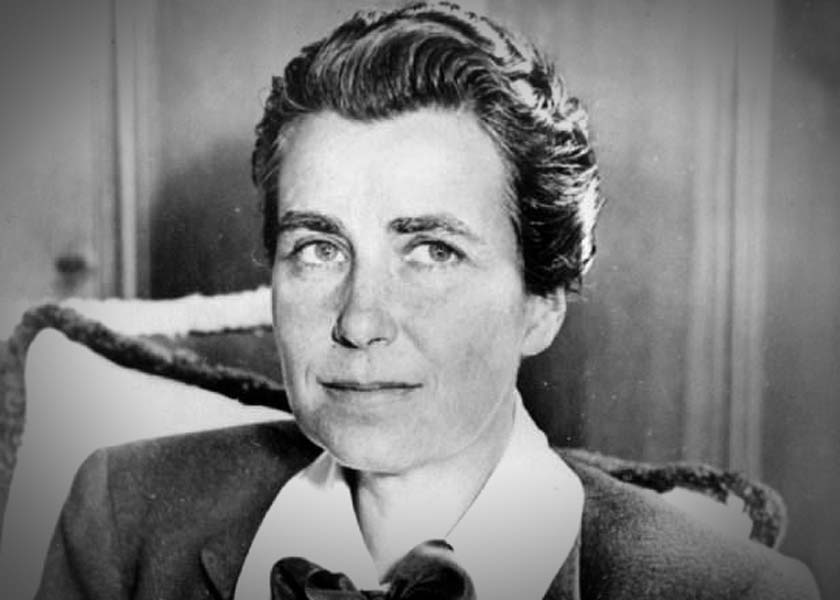

When she retired from filmmaking, Dorothy Arzner had been the only woman director in Hollywood for nearly twenty years (1927-1943). She had directed 17 feature films, at Paramount, RKO, Columbia, and MGM. Not surprisingly, her films are women's films, intended for the women in an audience, with a strong female protagonist. She directed leading female actors, including Clara Bow, Ruth Chatterton, Katherine Hepburn and Joan Crawford. Despite many studies devoted to her work, it is still an open question why she alone among the women in Hollywood had a career as a director.

Early Career

Arzner began her career just after WWI, typing scripts for Famous Players-Lasky, the progenitor of Paramount. She advanced to a position as the only cutter and editor at Realart Pictures Corporation, a small studio subsidiary of Paramount, for which she cut and edited 52 pictures from 1920-1922.

She was called to Paramount to cut and edit Blood and Sand (1922), a follow-up film for Rudolph Valentino, after his great popularity in The Sheik (1921). She filmed some of the bullfighting scenes for this feature, her first directorial experience. Director James Cruze appreciated her editing and writing skills and employed her to edit The Covered Wagon (1923), his best known film, and to write and edit Old Ironsides (1926).

Silent Films at Paramount Studios

According to Arzner, her directing career at Paramount resulted from her taking a job to write and direct at Columbia Studios. She had been writing scripts for Columbia Studios, and Columbia was going to hire her as a director. She had observed the directors at Paramount, including James Cruze and Cecil B. DeMille, and felt she was adequately prepared. She went to say goodbye to Paramount executives B.P. Schulberg (head in Hollywood) and Walter Wanger (head of New York). They asked her to stay and direct for them.

In January 1927, Arzner was assigned her first film. They gave her a production based on a French farce, The Best Dressed Woman in Paris. She was to write the script and direct Esther Ralston who had made a success in Peter Pan (1924). Arzner turned out a nice little picture, Fashions for Women (1927), giving appropriate close-ups of the beautiful star and showcasing the fashion show aspects.

After her next film, Ten Modern Commandments (1927), also starring Esther Ralston, was well received, Arzner was assigned to a Clara Bow project, Get Your Man (1928). This assignment indicates the confidence the producers had in Arzner's abilities. Bow was one of the top stars of the studio. This picture was known around the studio as the "all-woman production": Clara Bow was the star, Dorothy Arzner the director, Hope Loring wrote the screen story, Alice Laser handled continuity and Marion Morgan was the technical director for some museum scenes. It was many years before another Hollywood film would have such a designation.

Arzner's final silent film, Manhattan Cocktail (1928) featured one of the studio's rising stars, Nancy Carroll, in an entertaining melodrama.

Talkies at Paramount

Arzner had proved a reliable director, and she was assigned to ease Clara Bow into talkies. Before filming commenced, Arzner rehearsed the cast so they could learn their lines. Bow had a slight Brooklyn accent, but she spoke her lines satisfactorily. Arzner moved the film along at a speedy pace. Bow's vivacity was highlighted. The Wild Party (1929) received a good reception with audiences.

She directed two films with Ruth Chatterton, one of the most popular stars at the studio. Sarah and Son (1930) with Fredric March was a hit. Critics praised Arzner's restrained direction. Her next Chatterton film, Anybody's Woman (1930) was satisfactory, but not as successful. The film features a clever device to highlight sound, an electric fan blows a conversation across a hotel courtyard.

Arzner collaborated in writing her next film, Honor Among Lovers (1931). She was sent by studio to make the film in New York. It was intended to be a smart, high comedy, but is rather slowly paced and melodramatic. It starred Claudette Colbert and Fredric March. Arzner had seen March on stage (in The Royal Family of Broadway) and liked his work. He had also been cast in The Wild Party and Sarah and Son, and would appear in Arzner's final Paramount film, Merrily We Go to Hell (1932).

Arzner stated that she had no trouble with the Paramount producers because she was the only woman director. Many women worked for the studio behind the camera, as writers and editors and other positions. Arzner did not have much interference on pictures at Paramount; she made them her way. She had contracts for 3 years at a time, paid by the week. She had a regular crew for her films, including cameraman Charles Lang and costumer designers Adrian and Howard Greer. This system of picture making worked smoothly.

Arzner left Paramount in 1932. Paramount, as with most of the movie studios, had a large deficit (over $15 million) in 1932. Hundreds of employees, including B.P. Schulberg, made enforced exits, and the remainder took salary cuts. The studio offered Arzner a new contract with a decrease in salary, and she declined it. Paramount had new executives; the men who had supported Arzner had departed. She decided to freelance.

Freelancing

After directing nine films in five years at Paramount, Arzner never had a contract at another studio that lasted more than a year. In the remaining ten years of her career, she directed only six films. After two films made in her first two years freelancing, the time interval increased to two years and then to three years between the final projects.

Her first offer came from David O. Selznick at RKO, for Christopher Strong (1933). Originally the lead was to be Ann Harding, but she was taken out, and Arzner choose Katherine Hepburn who she had seen in the studio. Arzner felt that Hepburn was the modern type woman required for the role of an independent, courageous aviatrix. A lasting effect of the film was to create a screen persona for Hepburn as an independent, intelligent and courageous woman, sensitive and reflective. Arzner gave special attention to the performance of Billie Burke as a betrayed wife, the first of three Burke performances in Arzner's films. Arzner worked on the film in close collaboration with Zoe Atkins, who had written three films for her at Paramount in 1931.

Despite the efforts of director, writer, and actors, the film was not a success at the box office. The characters and situations were rather old-fashioned and the plot stagey. Arzner may have been unable to update it. At one time she called the film one of her favorites, but in later years she was critical of her own work and did not name favorites. She saw only the flaws.

Arzner's next film was for Samuel Goldwyn, an independent producer who had his own

Hollywood studio. Goldwyn had signed the beautiful Russian-born actress, Anna

Sten, as his star to vie with Garbo and Dietrich. Sten did not speak English when

she arrived in Hollywood and studied intensely before filming started. The story

chosen for her was Nana, based on a novel written in 1880 by Emile

Zola. The first director on the film, George Fitzmaurice, did not get along with

Sten and asked to be relieved. The scenes already shot were dropped. Goldwyn tried

to get George Cukor to replace Fitzmaurice, but Cukor had too many other

commitments. Goldwyn had seen Christopher Strong, thought it was a

good film and hired Arzner to guide Sten's performance. Goldwyn had several

writers work on the script, and they had produced multiple rewrites. Arzner, not

satisfied with the version she was given, had wanted a more important script. The

final version greatly softened the man-eating character of the novel's heroine.

Goldwyn gave Arzner everything she wanted in the way of sets, lighting and

cameraman, in return he hoped that Arzner could direct a star-making performance

from Sten. Arzner found that task impossible, stating that

The only thing I could do was not let her talk so much.

Nana (1934), Arzner's only film for Goldwyn, failed miserably at the

box office.

In October 1934, Arzner signed a contract with Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures as an associate producer, the only woman producer in films. In early 1935, Arzner was planning to produce and direct a film called Feathers in Her Hat to star Alice Brady. Arzner and casting director Bill Perlburg went to New York to test talent for the film. Nothing came of this effort, and Arzner's contract ended without completing any films.

In June 1936, Arzner was signed by Cohn to direct Craig's Wife, based on a successful stage play. She wanted Rosalind Russell, relatively unknown at the time, for the role of Harriet Craig based on her strong delivery of dialogue. Arzner, trying to be faithful to the intent of the play and wanting control of her film, kept the script from Harry Cohn's interference. Despite fine reviews for acting and directing, the film was not a big success.

In August 1936, Arzner signed with RKO to direct Ginger Rogers in a solo-starring film, projected to be a version of Mother Carey's Chickens. The initial start date was announced for October. However, filming was pushed back, and by November the film was postponed until January 1937. Variety noted that Arzner was using the time to work in her garden. Arzner's contract with RKO expired without completing the project. Mother Carey's Chickens was finally produced by RKO in 1938, starring Anne Shirley and directed by Rowland V. Lee.

Arzner signed a directing contract with MGM in January 1937. She was excited to make a film based on an unproduced play Girl From Trieste by Ferenc Molnar, about a former prostitute trying to remake her life. The film was to star Louise Rainier, with Joseph Mankiewicz producing. While preparing for the Rainier film, Arzner brought in the last few shots of The Last of Mrs. Cheyney (1937), starring Joan Crawford and William Powell. The title of the Rainier film was changed to Once There Was a Lady. In May, Arzner, who did her own location shooting, went to the June Lake area of the Sierra Nevada looking for suitable locations to represent the Alps. In June, filming commenced with Joan Crawford starring. Now called The Bride Wore Red, the script was lighter and frothier than the Molnar play. In later years Arzner stated that she had not liked Louis B. Mayer. He had asked her to work with Crawford, whose popularity was declining, and made promises about the film that he did not keep.

An amusing anecdote from the filming concerns Crawford’s first scene. A rich man buys Crawford's character, Anni, dinner. The food contains meat; Anni has always been so poor that meat is a luxury she has seldom eaten. Crawford ate the stew over and over as Arzner tried to figure out just how she wanted it.

Arzner was uncomfortable at MGM working on mammoth sets in a lavish production. She considered the film rather synthetic; it was not a favorite of hers. Reviews and returns were tepid. Crawford is acceptable, but the part would have suited Rainier better.

Several years passed. In May 1940, Arzner took over the direction of Dance, Girl, Dance at RKO. Roy Del Ruth, the original director, withdrew from the production after disagreements with the producer Erich Pommer. The Del Ruth footage was discarded, and Arzner, consulting with Edith Noyes, reworked the script to define the central conflict as a clash between the artistic aspirations of Maureen O'Hara's classical ballerina and Lucille Ball's burlesque dancer. The resultant film received unenthusiastic reviews, was a poor audience draw, and did not return its cost.

Renewed examination of the film has brought appreciation of its merits. In 2007,

Dance, Girl, Dance was preserved by the Library of Congress in the

United States National Film Registry. Upon registry, the film was described as

Arzner's most intriguing film,

a meditation on the disparity between art and commerce.

After another three years, Columbia producer Harry Joe Brown brought in Arzner to direct a story about Nazi-occupied Norway, First Comes Courage (1943), starring Merle Oberon and Brian Ahern. Arzner had nearly finished the film, including all the location shots and the fight scenes, when she came down with pneumonia and had to withdraw. The film was finished by another director. Despite the strength and conviction expressed by the story and characterizations, the film was unsuccessful in attracting an audience.

Arzner was sick with pneumonia for nearly a year. After her recovery, she retired

from directing. Her explanation was simple: Pictures left me.

Later Career

Retirement from film directing did not mean retirement from working. Arzner continued her association with filmmaking in areas other than the movie studio.

During World War II, she worked on a series of short films for the Women's Army Corps and trained four women to cut and edit these films. The actors came from Samuel Goldwyn's stock company. Projection of the films was restricted to WAC training.

In 1950, Arzner became associated with the Pasadena Playhouse, a well-known theater company in Southern California. She produced some plays and occasionally directed one. In 1952, she joined the staff of the Playhouse's College of the Theater Arts as the head of the Cinema and Television Department. She taught the first filmmaking course offered by the college.

Arzner was a friend of Joan Crawford. In the late fifties, Crawford was married to the head of Pepsi-Cola. Crawford's influence helped Arzner become a consultant on entertainment and commercials for Pepsi-Cola with its advertising agency, Kenyon & Eckhardt. Arzner directed more than 50 Pepsi commercials, many of them featuring Crawford herself.

In 1961, Arzner joined the UCLA School of Theatre Arts in the Motion Picture Division as a staff member and student advisor. She spent four years supervising advanced filmmaking classes before retiring in June 1965.

Personal Life

It is accepted that Dorothy Arzner was a lesbian, as indicated by her dress and demeanor. She did not talk about her private life but made no effort to hide her sexual orientation. Many photographs show Arzner in her typical pants and jacket or straight-cut suit (when filming she often wore a different suit every day). She had a forty-year relationship with dancer and choreographer Marion Morgan. Morgan, ten years older than Arzner, had been married and had a son. She led a dance troupe and choreographed dance sequences for some of Arzner's early films. In 1930, Morgan dissolved the dance troupe and moved with Arzner into a home in Hollywood. They were companions until Morgan's death in 1971.

While she lived in Hollywood, Arzner was part of the Hollywood scene, attending film openings and other events or dining in public with Hollywood personalities, often with good friend Billie Burke.

By the 1970s, with the increasing push for equal rights for women, interest in the status of women in the film industry came to the fore. Much attention was given to the fact that Arzner had been the only female director in Hollywood during the 1930s. Her work was shown at retrospectives of women's films, including the First (June 1972) and Second (September 1976) International Festival of Women's Films at the Fifth Avenue Cinema in New York, and Women's Film Festival (June 1974) sponsored by the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Art Institute.

In 1975, Arzner was honored with a retrospective by the Director’s Guild of America as part of their Pioneers series. For many years, she had been the only female member of the Guild. At the event, the guild honored her as strong-willed, clear-eyed and unsentimental, tough in fighting the front office. Technicians Edward Wheeler and Artie Jacobson who worked with her on The Wild Party, her first sound film, noted that she won the crew's respect by her competence in knowing how to make a picture. Director Robert Wise, who had been an editor on Dance, Girl, Dance, described her troubles with producer Erich Pommel and her determination to control her own film.

In her later years, Arzner left Hollywood and moved to the desert. She died in LaQuinta, a desert town near Palm Springs, CA.

Career Consideration

Arzner was the only female director in Hollywood from the 1930s to the early 1940s. Her professionalism, competence, and position as an A-list director were unquestioned. The majority of her films were made at Paramount where she was continually active, starting with silent films and through the transition to talkies. The producers at Paramount at the time, especially B.P. Sculberg, were her backers. Her output slowed considerably during her years freelancing, and there were long periods between films in her late career.

At Paramount, Arzner had a typical director's schedule and made nine films in five years. At most, she directed one film a year during the final eleven years of her career. Why did Arzner's filmmaking decline in the freelancing years? Quality does not seem to be a factor. Her films are of about the same quality as those of many other A-list directors. Box office returns may have affected her employment. The profit/loss on her films was quite mixed; while some films made a profit, others lost money. The response of male producers to a woman director may have been important. A female director may not have been a first, or even second, choice of male producers, except for her initial backers at Paramount. Her determination to make films her way may also have deterred many producers.

An examination of Arzner's films finds them solid and workmanlike. Thematically, her films are generally women's films, not feministic particularly, nor looking for equality, but emphasizing the problems facing a female protagonist and often with attention on women's relationships with one another. Her understanding of feminine actors allowed her to aid their portrayal of lifelike characters.

Her best films are probably the very successful Sarah and Son, with Ruth Chatterton, Christopher Strong, with a notable performance by Katherine Hepburn, Craig's Wife, for which a good play made a strong film, and Dance, Girl, Dance, with complex relationships between the female characters.

Interviewed for Variety in 1933, Arzner stated that film direction is just a job. She told the interviewer that the subject of women in the film industry did not interest her particularly; in fact she did not like to talk about any phase of the picture industry. She regarded movies as transitory and evanescent, an unsatisfactory means of expression. She put everything into making a film, but once it was finished, she forgot it. Films, in Arzner's view, were created quickly for quick consumption, meeting immediate needs before finishing its short lifespan. She had no idea of lasting value or of review of films in years to come (including her own) and did not consider film an art form. Her place was to make and finish a film and not attempt to leave an artistic monument to posterity. These ideas may be reflected in her carefully designed, but not consciously artistic, films. It is probable that she continued to hold this outlook for her entire career. It may have served as a personal shield against the responses of a male dominated industry to its lone female director.

Since the 1970s, Arzner has been the subject of study by feminist film critics and queer film theorists, although these aspects of her work are beyond the scope of this biography.

Further Reading